Long-term Richard James client, British GQ editor-in-chief Dylan Jones recounts his experience of commissioning suits, from houndstooth to Prince of Wales check, and even a velvet smoking jacket. Taken from the in-store and online now Richard James book.

Our relationship started, naturally enough, with a wedding (although not our own, obviously). It was 1997 and I was about to get married and, having had suits made for me since God was a boy – OK, since the mid-1980s – it seemed to make sense to commission the very best wedding outfit I could.

I started having suits made for me because I couldn’t find anything to fit me. In the early 1980s, unless you were built like an American footballer, and had incredibly broad shoulders, suits didn’t really work. Especially if you were as tall and as skinny as I was. Even though all suits in the early-1980s had humungous shoulder pads secreted about their person, on me they simply looked like someone had wrapped a beanpole in a bed sheet. So at some point I decided that I needed to get some suits that made me look like a human, rather than a cartoon.

However, I have to admit that as soon as I started having suits made for me, I moved around a bit. I was – hangs head, and looks ashamed – rather unfaithful. Well, not so much unfaithful, as serially monogamous.

I started in 1984 with a lovely old tailor called Jack Geach in Harrow, who used to make suits for Teddy Boys, and who was rather surprised by some of the things I asked him to make, like herringbone drape jackets, for instance, with bright red peg pants. Then a year or so later I moved a little closer to London, alighting on a man in Kentish Town, an ex-boxer who used to make suits for the likes of Spandau Ballet and Wham! He made suits for lots of people who were on Top of the Pops at the time, including one notorious singer who used to ring up a store in South Molton Street called Bazaar, and ask for a dozen suits to be sent round to his house in order for him to notionally choose something to buy. Then he’d choose one, ask for a massive discount, and send the others round to Kentish Town to be copied.

Then, after a few years, I moved again – getting closer to Savile Row all the time – this time to Timothy Everest, the sagacious tailor based in Spitalfields. This was the early 1990s, and I was now working in newspapers, and so needed some rather more formal suits, outfits that weren’t going to scare the horses or the sub-editors. He made me half a dozen navy blue pinstripe suits that I wore until they fell apart, and I loved every one of them.

By 1997 however, and with my wedding coming up, I decided I needed to move to Savile Row, to Mayfair, to the very epicentre of bespoke tailoring. So I did. With a vengeance.

I wasn't especially interested in going old school, as I had a very clear idea of what I wanted, and didn't want any arguments. These days the legacy tailors in the Row are far more accommodating (they have to be), but in those days they tended to do things rather more traditionally, and I was adamant that I wanted something with a twist. I didn’t want to be steered in a particular direction, as I had very clear ideas of what I wanted. And what I wanted was something modern. Get me!

Richard James and his business partner Sean Dixon had already been in the Row for five years, yet they were still being treated like interlopers by many of the old-timers on the street. Because James and Dixon designed suits made out of denim, out of camo, pretty much out of anything they liked, the Row tended to sneer, and were openly disparaging about them. Shame on them.

James and Dixon couldn’t have cared less, however, and had already built up a healthy fan base, a clientele who understood that in order to be well dressed one didn't have to adhere to old-fashioned ideals. One didn’t have to lope around in a three-piece pinstripe with scuffed Oxfords and an old school tie covered in dark brown soup from one of the fustier clubs in St James’s.

My suit, in hindsight, was actually rather traditional, being a two-piece bright blue mohair creation with slanted pockets and a purple lining. Actually it wasn’t exactly a loud bright blue, but perhaps not the kind of blue one might have worn at the time in a boardroom. I've still got it today – it’s nestling in the back of my wardrobe like a ceremonial trophy – and although I've had the waist altered a few times, it appears to have shrunk as there is no way I can fit into it anymore. It hangs in my wardrobe, and will until I die.

Since then, I must have commissioned at least 20 Richard James suits, and although I have occasionally veered up and down the Row to sample the delights of their competitors – some of whom are exceptionally good – I always come back to Richard James, as that is where I feel most at home. Over the years I have experimented, although I have to say that the ones I still wear the most are the ones that look most like my wedding suit. So while I have commissioned Prince of Wales checks, houndstooth, pale blue summer suits, herringbone tweed, burgundy velvet smoking jackets and all manner of extravagances, it is the rather more prosaic navy blue two-piece that I return to again and again.

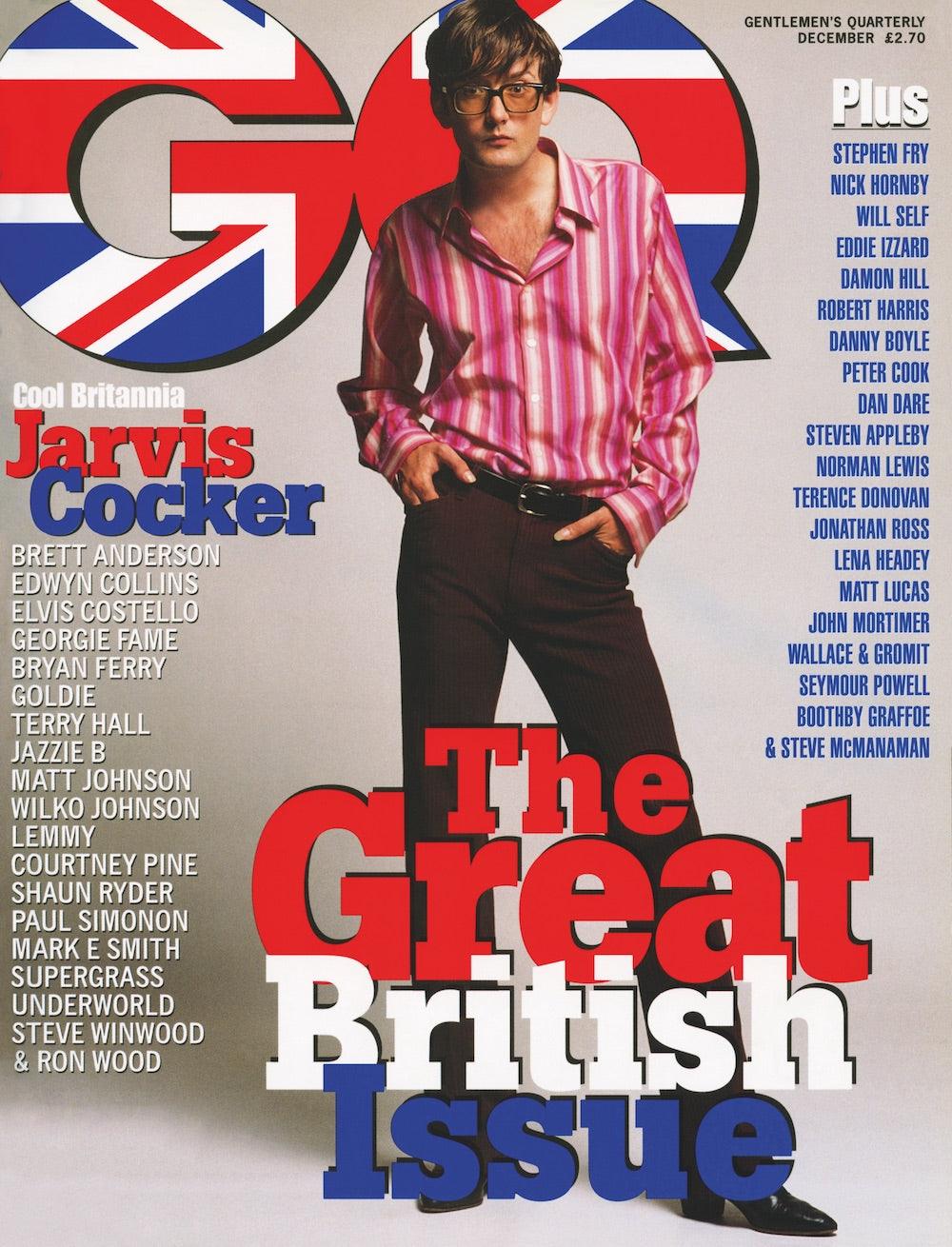

I joined Condé Nast in 1999, and as the editor-in-chief of GQ I've always gone out of my way to feature Richard James as often as I can in the magazine. Well, as often as I can without it looking slightly suspicious. Why wouldn't I? After all, they are some of the brightest stars on the Row, even if, after 25 years, they are still considered to be interlopers. We have done countless portfolios of their clothes, often draped around the recently notable and the legendarily famous (and sometimes both!), and always included them in our regular round-ups of where to go, what to do and what you should wear when you get there. In some ways I suppose they have almost become like family, at least you would think so judging by the number of on-point Richard James suits I see striding around the GQ office, looking confident, colourful and borderline pleased with themselves (or maybe that's just the staff). In fact, if I'm ever asked what suit I am wearing – and it might surprise you to learn that this happens remarkably often, and during peak season, on a daily basis – unless it's patently obvious that it's designed by someone else, I tend to say ‘Richard James’ almost by default. It's just easier. Flying the flag and all that. As I have a wardrobe full of approximately 50 navy blue suits, this is perhaps not as unusual as it could be. And who knows? Often I am wearing a Richard James suit.

I have had so many suits made by Richard James, and enjoy wearing them so much, that by now I really should have encouraged them to start making them with cleverly calibrated elasticated waists, because that way I could occasionally still fit in to some of the ones I commissioned towards the end of the last century. Not that the staff ever intimate that I may be little thicker around the waist, of course, because whenever I'm being measured for a new suit, whoever is doing the measuring tends to go rather quiet when he wraps the take measure around the bottom of my stomach (that place where the waist is meant to be – well, mine anyway), circumventing it rather than circumnavigating it. And whenever I ask what the hideous truth actually is, I'm always reliably informed that it's touching 34. Which, as I tell them on a regular basis, is obviously a barefaced lie.

It’s not just suits I have, either, as my wardrobe is also full of extravagantly coloured and curlicued ties, block colour shirts that are now fading like the parties I wore them too, bright neon V-neck sweaters that still come out every winter weekend, and ridiculously pointy shoes that I can never bear to throw away. For a while I think I looked a little like a mannequin that had somehow escaped the clutches of the assistants, but this was never something that bothered me unduly. After all, if you're going to dandify yourself, there are worse ways to do it. I'm actually wearing a Richard James tie as I write, a swirling pink camouflage tie I bought probably 15 years ago. And each time I wear it, someone will clock it (and I don't just mean people who work there). In fact, the more I think about it, I'm fairly sure I ought to be buried in a two-piece navy Richard James suit. With a showy pocket square and a shouty tie, of course. Although I would like to add that I only really want this to happen at the appropriate time, ie when I'm dead, not just pining for the fjords or feeling a little under the weather.

I'm proud of my association with the brand, because it is representative of genuine transformation. James and Dixon have actually both been pioneers in their industry, even though they tend not to shout about it. Ever since the 1960s, British men have broken their own sartorial codes, often driven by the influence of youth culture. For years, though, Savile Row appeared to be impervious to change, uninterested in the swirl of sartorial egalitarianism that was engulfing the rest of the city. Sure, the occasional rock star might fall out of his Bentley before ordering a dozen bespoke suits from the likes of Tommy Nutter, or Anderson & Sheppard, but largely the Row was an oasis of obsolescence. This was strange, as the rest of Mayfair was certainly getting with it. Mayfair has often been the home of dandies and show-offs, especially during the 1960s, when nascent pop stars roamed the neighbourhood in search of entertainment and expensive trousers. At this time the postcode seemed to encourage a kind of sartorial extremism, almost as though it were some sort of fashion theme park. Over in Soho, on the other side of Regent Street, the Carnabetian Army may have been marching in time to the metronomic reveille of seasonal trends, but in and around Berkeley Square, the fops, coxcombs and recently emancipated young musicians from the suburbs were wandering around in bright feather boas, snakeskin boots, Regency suits, kipper ties, extravagant scarves, fur coats and feathered hats.

But not Savile Row, which for years appeared to deliberately shun the sartorial whirlwind around them. Until Richard James moved in, that is, and helped set about a revolution.

The fact is that men have changed how they dress: we have a new generation who shop more like women, who are sophisticated consumers, and who have no qualms about spending money on clothes. Even 20 years ago this wasn’t the case, as most men were still a little scared by fashion; now they expect to buy great clothes at every price point, from entry level to luxury.

These days it is quite common for a man to have a suit made, whereas 25 years ago, you did so only if you were the sort of person who patronised Savile Row. And back then you had to be a very particular type to visit the Row – a banker, a politician or a barrister. Or maybe that rock star. Nowadays, anyone can go to a Savile Row tailor. Not only has the industry changed, but the customer has changed, too. Britain today is more classless, more racially mixed, and far more attuned to fashion as an indicator of personal sensibilities. This is especially true of menswear. There are also more menswear designers these days, and more brands making clothes specifically for men. Globally, the menswear market is in its ascendancy, as luxury brands and mass-market labels discover that more and more men are prepared to buy clothes seasonally in the way that women have done for decades. But then, menswear is something we are extraordinarily good at. It is an intrinsic part of British heritage and history.

James and Dixon not only know this, they have also helped espouse it, creating a quiet revolution from their Savile Row premises, encouraging new generations to sample the delights of bespoke tailoring without making a song and dance about it.

So congratulations on surviving 25 years in the Row. No small feat, no small achievement.

Dylan Jones is editor-in-chief of GQ and the chairman of London Fashion Week Men’s