The Evolution

With bold designs, innovative cuts and a multitude of colours, Richard James's arrival in Savile Row 25 years ago marked a shift in the way the world viewed men's tailoring, says Nick Sullivan

Rumours of the inexorable decline and eventual demise of Savile Row as an institution have been circulating for several decades. It is still there however. Here in New York, at certain times of the year, it’s impossible to swing a cat without hitting a head cutter or a shoemaker from London or Milan bent over his business: measuring, tweaking, pinning or primping some unique new creation into bespokeness for an eager roster of successful men. The competition between the twin pillars of men’s style, the ethereal otherworldliness of bespoke and the immediate excitement of ready-to-wear fashion, has been the driving force of the evolution of style since the year dot. And certainly since I got myself mixed up in it.

It was about that time that Richard James – having garnered much critical praise for his early catwalk collections shown in Paris, but not much in the way of cash flow – refocused his dream in a more manageable way, and opened his first store. The store was on sleepy Savile Row not in trendy, bustling Soho. With very good reason. One day, shortly before it opened, I went to have a look. Through the plate glass windows of number 37a, I could see things were soon going to be very different on that block.

If you’re like me, you know that Savile Row is not dull and dour and full of retired, fusty Major Generals. Savile Row, you see, is sexy. It’s not sexy because it’s traditional; it’s change that makes Savile Row sexy. The best and brightest hope for Savile Row is not keeping out the outsiders, its letting them in. Provided their heads and hearts are in the right place.

New blood on the Row – and the new ways of thinking about men’s clothes they bring with them – has always served to throw the skills of the tailors and cutters into even greater relief.

New blood on the Row – and the new ways of thinking about men’s clothes they bring with them – has always served to throw the skills of the tailors and cutters into even greater relief.Richard James’s arrival in 1992 mirrored in many ways that of Tommy Nutter in 1969 (at No 35a), which brought consternation but in its wake, also rock stars such as the Stones and The Beatles and a hipper sense of what Savile Row could do if it was so minded. Even then, such changes of direction were not new. When Dutch tailor Frederick Scholte moved into No 7 in the early 20th century, his softer ‘drape cut’ – free of the ramrod stiffness that had clothed the officers of empire – ushered in a seismic shift in dressing, championed by the then Prince of Wales and further refined by the Swedish import he had mentored, Per Gustaf Anderson, co-founder of that hot-bed of sartorial rebellion, Anderson & Sheppard.

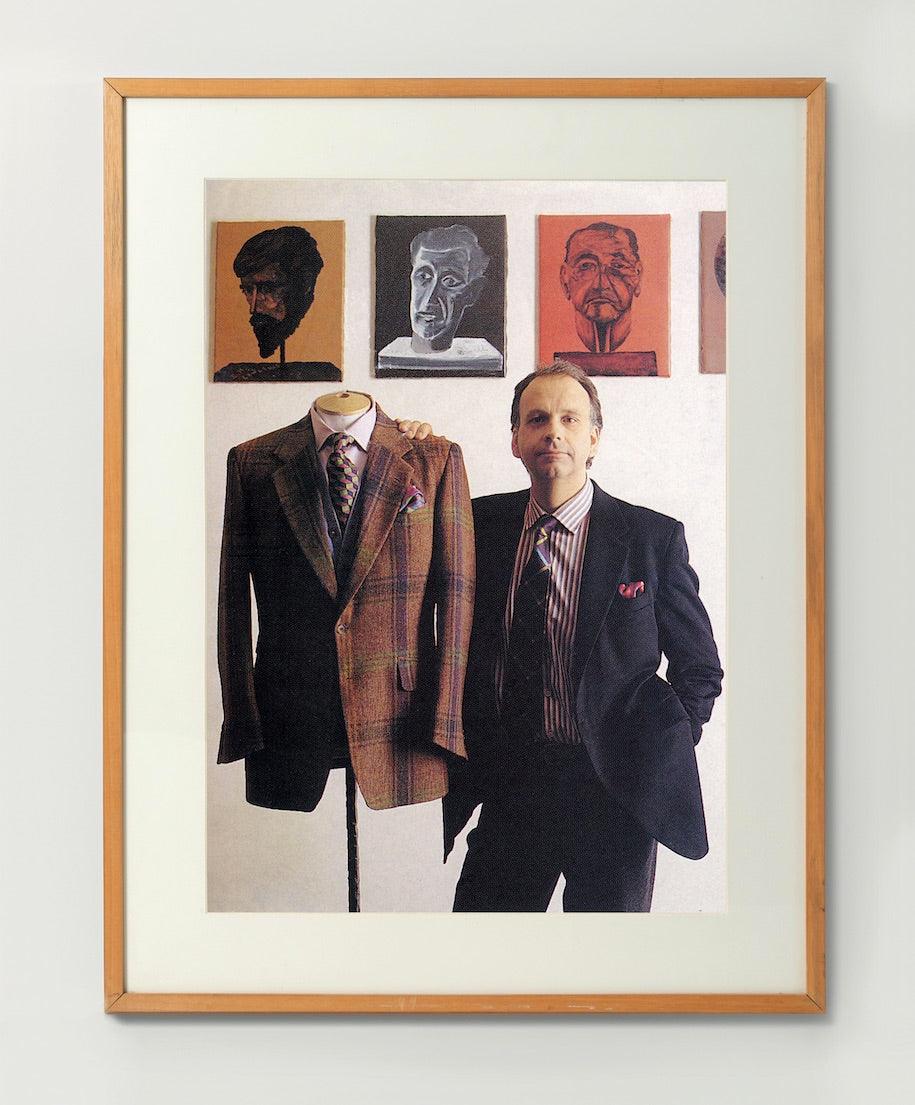

Richard James was not, of course, a tailor. Instead he used a worldly designer’s eye to reimagine something that is quintessentially English. Through Richard, I learned about oddly arcane details like Frogmouth trousers and Fishtail cuffs that came from the depths of Savile Row’s military canon. In his hands, they looked revolutionary. It was like peering at Savile Row through special glasses, both a throwback and a leap forward – jackets were light but well-fitted at the waist, at a time when big-name designers were into boxy, roomy blocks and more commercial brands were still locked into the shoulder-padded 1980s. At Richard James everything but the shoulders were exaggerated, from the length of the skirt, the cuffs and, most of all, the colour. And my, what colours! An early purchase of mine was a tie that was a dazzling repp silk extravaganza of pink, yellow and green cubes that seemed to dance in 3D in front of the eyes; sunglasses were advisable if you had the misfortune to sit across a lunch table from me back then. I accessorised with an emphatically yellow sorbet double-cuff shirt, also Richard James. When I finally nailed my first tweed jacket it seemed the apotheosis of Richardness, of everything I loved about his brand. Overblown three-inch windowpane checks danced on a fuzzy field of green Shetland, like a photograph of a Scottish hillside in a springtime dream by Walt Disney. Unfortunately, the moths liked it almost as much as I did. But I still think of it from time to time. Richard James’s suits, of course, were more sober but they had enough of his unusual signature details to give them an edge and they found an appreciative audience among young men around London who wanted to have it both ways – to have both tradition and innovation in the same look.

I’ve calmed down a bit since then, especially since moving to New York 14 years ago. When I got here, I admit I rather played that ‘Englishman in New York’ thing, wilfully clinging to a two- (and occasionally three-) piece navy suit worthy of Bond, and a Jermyn Street shirt and tie, sweating pretty much half the year on the subway, until one day some half-wit asked me if I was a publisher. This also coincided, a decade ago, with a wholesale shift in men’s fashion that reacquainted men with functional tailoring, democratised the dandy and, in so doing, took all the fun out of dressing well. James’s collections have evolved too, reflecting the changing expectations men have of their clothes, with a broader range that has as much casual clothing as formal, but still with those signature colours.

The opening of a discreet new Richard James store slap-bang on Park Avenue, a stone’s throw from the designer shops on 57th Street, seems like another pivotal moment for Richard, 25 years on from when he first set out his stall on Savile Row. I think it’s very timely. Because it coincides with the first green shoots here, and in Europe, of a new trend towards something simpler than the fast fashion we’ve seen of late; perhaps it’s an alternative mindset rather than a replacement. In New York, the bespoke tailors continue to do a roaring trade; at retail, new stores are as likely to be about tweed as they are about sneakers. It’s something sober yet edgy that relies all the same on that vital cocktail of fashion and substance at which Richard James has always been rather a dab-hand.

Nick Sullivan is Creative Director at Esquire.